AI: solvent and accelerant on the route to a CustomerX world

Separate sectors in D2C commerce were bridged by data exchange, commerce media and API-first platforms. AI at once dissolves the remaining membranes and accelerates commerce. CustomerX is our answer.

For decades, commerce has been organised around sectors: retail, travel, media, leisure, finance, health. The origin of these sectors was simply that the products and services were constructed, produced and delivered differently: fresh produce to a store (Grocer), versus renting of clean and tidy rooms (hotels) or operating a current account such that customers can save, pay and manage their salaries (banks). This is obvious.

Over time, however, the operational processes have become invisible to the customer as the service and experience layers have grown ever slicker and more capable. It’s entirely normal for a customer to have a great experience buying clothing and then denigrate a hotel because there are not dozens of photos of each individual room; or if we can order a grocery delivery slot with hour precision, should ’t booking a service engineer to fix our washing machine be just as slick? Customers are adept at extrapolating excellence in one domain into expectations in another.

As mobile becomes the main access interface (or ‘surface’), it’s natural for the customer to expect the same service wrapper, irrespective of the fact that picking a delivery date on Amazon is substantially different from reserving a room for two people over 4 nights, seven months in the future.

Being a modern consumer is the result of much training. We need to understand the dynamics and parameters of each service – hotels, travel, tickets for a gig, grocery, luxury brands, online gaming or streaming – and then we can ‘drive’ the interface effectively.

Consumers never truly inhabited those sectors, but until recently, the operating and delivery friction forced them to behave as if they did.

That friction is now disappearing, and – from a retail perspective – we are at an epochal point, like the arrival of digital commerce in the early noughties. To be clear, I should say “the arrival of digital interfaces to commerce” – the web put new levers in the hands of the customer, even though businesses had been ‘computerising’ for decades. The computerisation was locked inside the business until the arrival of internet commerce.

Artificial intelligence is not itself the cause of this change, but it is its catalyst. AI acts simultaneously as a solvent — dissolving the membranes that once separated sectors — and as an accelerant, speeding up how quickly consumers reallocate time, money and attention across their lives, just as retailers process, share and monetise data and services, amped-up by AI.

AI in the customer’s hands is both a solvent (dissolving the membrane between sectors and shopping processes) and an accelerant (fuelling its own effects). As the art and practice of selling direct to consumers is no longer constrained to “the retail sector”, our response is CustomerX, a commercial approach where we collaborate, copy and compete across (former) sectors for the customer’s discretionary spend.

Let’s look at the dissolution of sectors, and how we arrived at CustomerX, starting with the customer’s money.

Where UK households spend their disposable and discretionary money

UK household disposable income is finite and, in real terms, under sustained pressure. According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), the majority of household spending is absorbed by a small number of essential life needs.

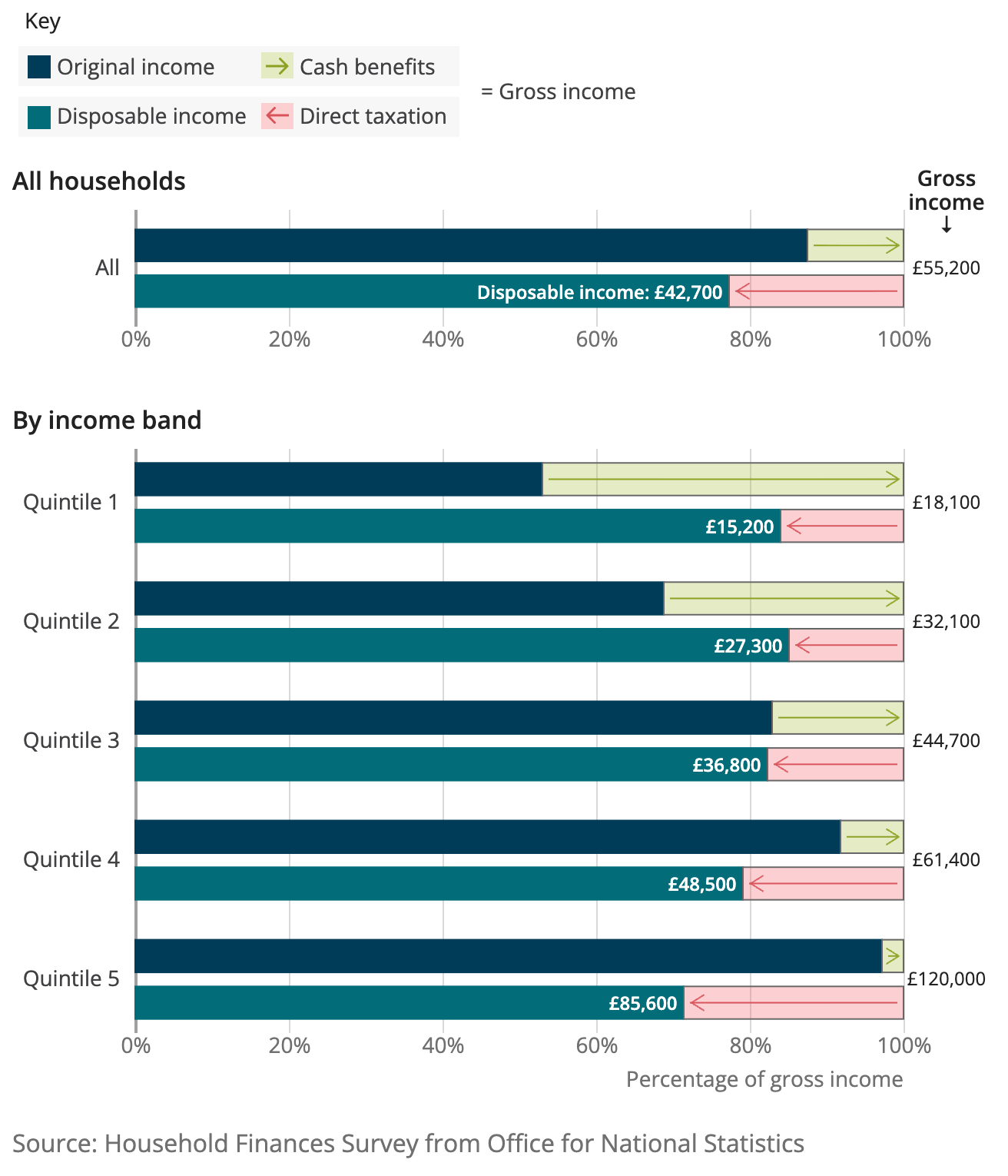

Disposable income in the UK is c. £ 42,700 per family on average. Of this amount, the discretionary element is lower, at more like £30,000, since housing, transport, and a main element of food purchases are neither optional nor can they be flexed to zero each week on a whim or to economise. All spending exists within a constrained discretionary envelope.

Citing an annual figure is misleading since it implies that consumers have access to their annual amount in one go and can make optimised allocations. In reality, a monthly or weekly payment cycle means free cash is eliminated by unexpected or seasonal spending.

I’ve created an extensive footnote with the source of the disposable income1 and some references for the category definitions and UN/OECD data sets.

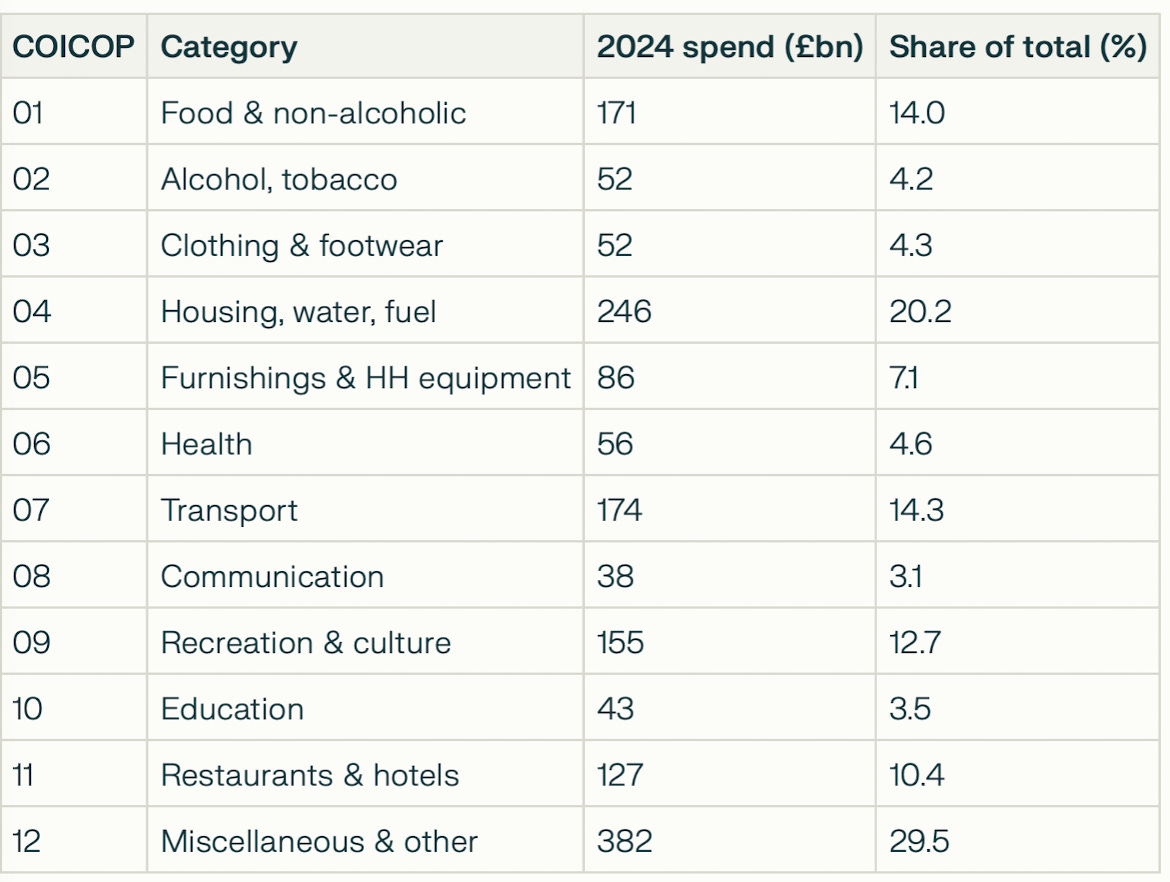

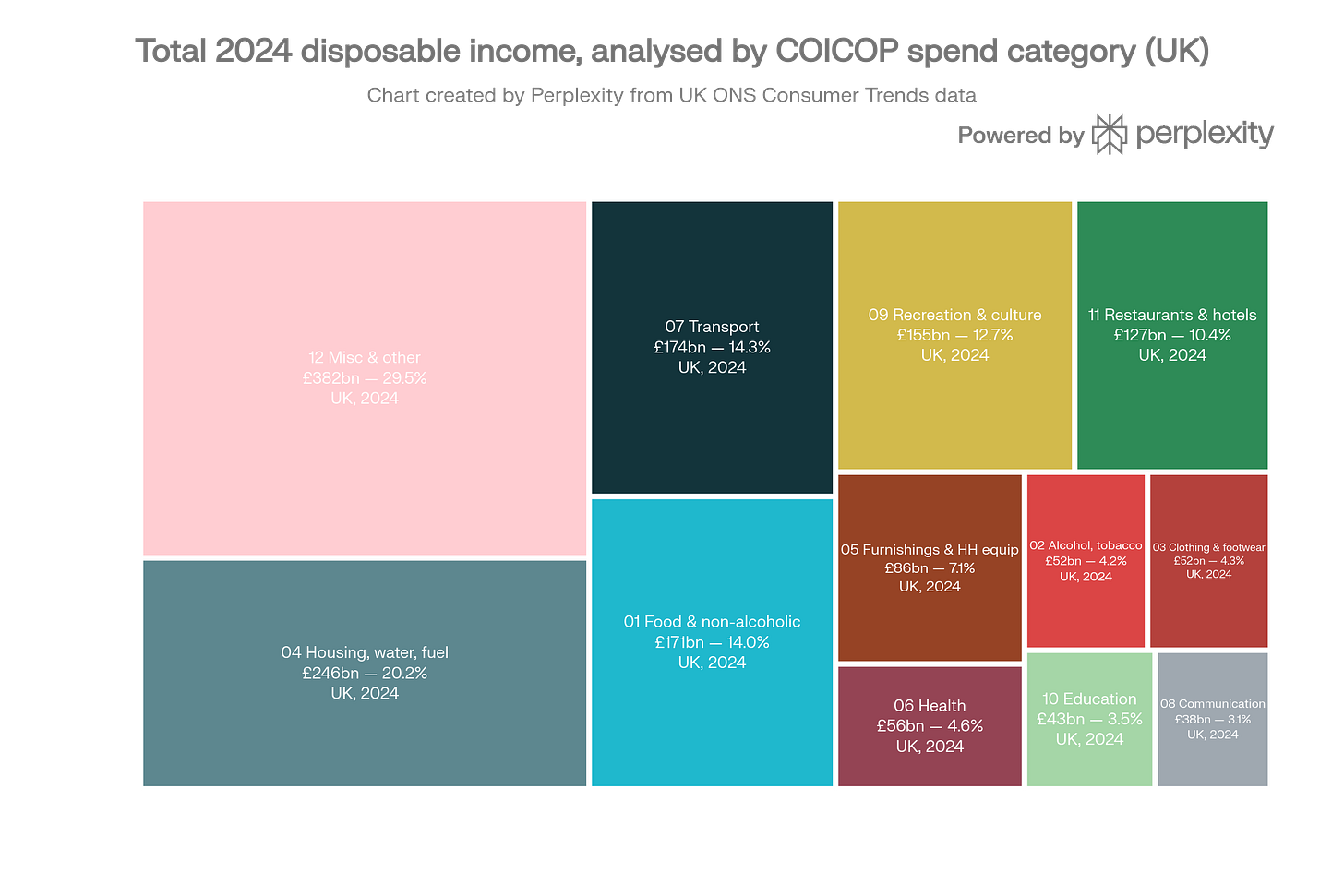

The approximate UK household expenditure split (by the UN-defined ‘Classification of Individual Consumption by Purpose’ or COIPOC, for 2024, citing total annual spend in £GBP, sourced from ONS is below - see footnote for fuller information):

Critically, consumers do not allocate this money by sector. They allocate it by life need.

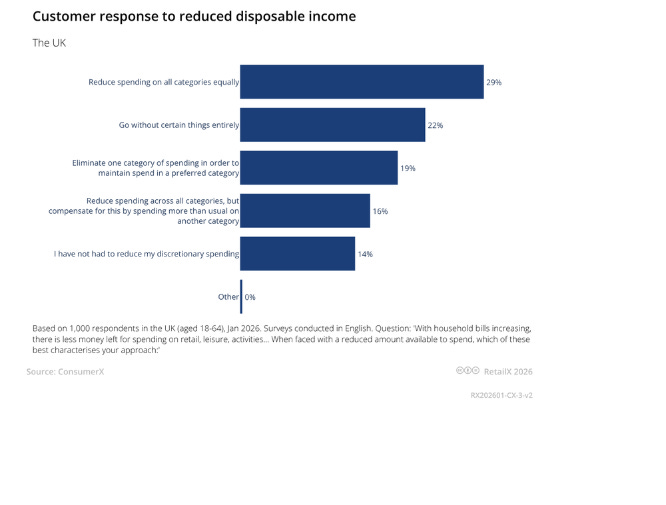

In not-yet-published research this week from RetailX, we asked customers how they would likely respond to reduced disposable income, and the flash results (below) show that after the initial reduction/elimination of spend, the option to reprioritise spend across categories was selected by 35% of respondents.

Why sectors existed at all

Sectors did not emerge because consumer needs were fundamentally different. They are a function of the fact that the underlying product types and services are fundamentally different and were challenging to connect.

Physical supply chains, property and zoning rules, fulfilment models, regulation and measurement systems enforced separation. Retail sold goods. Hospitality sold time-slices of properties and locations. Transport sold space on a vehicle from A to B. Media sold attention. Banking made your cash under the bed open to transactions. Each sector has its own infrastructure, capital, and operating expertise.

Consumers learned to think in categories and sectors because the world required it. Consumers adapted to the interfaces and affordances of the operators, typically fitting in with the operator’s conveniences and constraints.

Back ends are optimised, while front-end interfaces have collapsed

Operations, logistics, fulfilment and compliance remain deeply sector-specific. But discovery, evaluation, payment and loyalty have converged into shared decision layers, with surfaces like mobile rendering every request as a similarly slick, under-your-thumb experience.

From the consumer’s perspective, choosing a meal, a film, a fitness habit, or a short break often feels structurally and procedurally identical until the moment of fulfilment.

Voice and agentic interfaces further remove the customer from the button-clicking and configuration trails of today’s buying process. Requests are more task-oriented, comparative and conjoined.

Booking a restaurant (date, seats, time options; menu choice, occasion, details, card) are the same as a hotel (rooms, occupants, extras), a grocery slot (time, upsell, completion), or a plane ticket (class, options, seat). Despite the very different operational realities, the configuration processes are slick, similar and locate the service in space and time. All under one’s thumb, while the customer expects each to be as easy as the other.

Back ends remain vertical. Front ends have gone horizontal.

The long erosion of the funnel

This convergence did not begin with customer AI (although machine learning and AI behind the scenes certainly enabled cross-sector coherence).

Customers have increasingly been able to make ‘leaps’ across sectors and COIPOS categories. Performance marketing technologies, real-time attribution, identity resolution, on-platform checkout, retail media and CTV all contributed to dismantling sector boundaries at the point of intent. In parallel, marketplaces, portals and service layers (like Deliveroo) provided a service layer to connect across categories.

Consumer AI matters because it arrives after this convergence — and accelerates it. Now an AI interface can consider, hold, compare, suggest and action a broad intent (“friends coming round for a pizza and to watch Traitors tonight” or “getting me and my 2 kids to southern France by car in time for Granny’s birthday” - see my earlier post on this:

In retailing, the reality under customer-controlled AI is that when decision logic becomes horizontal, sector-based pricing power weakens. If we can no longer contain a customer wholly and exclusively within our transactional process then the ‘funnel’ and ‘conversion’ no longer perform according to our investment and ROI expectations.

Horizontal: the customer’s reality is optimising across life

Consumers do not generally want to make isolated, sequential purchase decisions. They are managing portfolios of time, money and emotional return across their lives.

A visit to a mall involves several stores - from food to fashion, leisure to functional, for the shopper and for her family and friends. A thought about a holiday while looking at spring fashion, or a memory to get healthy snacks for a child’s lunchbox, whose birthday is within a month, and so presents are under consideration… all of these thoughts must be ‘held’ until the shopper is physically able to consider and transact. In the mobile-commerce world, we can shop for fashion inside a frozen food store if we wish. In the agentic world, our digital sprite can go beyond ‘Buy x, buy y and consider other options.

A takeaway competes/compares/considers what’s in your fridge, what’s available on a streaming service, the money in your bank account and your friends’ preferences. A gym session booking competes with a smartwatch data set and a walk with coffee and a friend. A holiday competes with home improvement and local experiences.

The current model of mobile-first, under-your-thumb shopping captures purchases but not the life narrative and choices that inform them.

Substitution, combination, and alternatives all now happen continuously in the customer’s conversation with her trusted AI services, not cyclically.

AI shopping agents make decisions in real time, but as retailers, we aren’t privy to their logic or intent. Our analysis (of the part we can track - arrival, query, checkout or abandon) is like Plato’s cave shadows2 - an incomplete and impoverished version of a rich reality.

The customer is optimising ‘horizontally’ across her life: leisure, family, friends, fitness, and socialising. We collect and share data to understand and influence her choices, but agentic AI shows us less of her thinking and motivation than we are used to.

AI as a solvent and accelerant

As a solvent, AI dissolves the need for the customer to understand categories, sectors and retail verticals. Products and services are abstracted into outcomes, and become part of a solution, rather than the primary purpose of a narrow shopping journey.

AI dissolves the membranes between sectors, rendering them initially more pliable, less distinct and then just gone3…

AI also acts as an accelerant - able to consume and synthesise more product information, more options, more combinations that a human thumb-shopper could do. AI compresses comparisons, normalises substitutions, and speeds up the reallocation of options and services across life-domains.

AI is not the fire of commerce in this analogy: the customer’s desire is the spark, and her disposable income is the fuel. AI is the lighter fluid on fuel that eases and accelerates commerce.

Business models cross the membrane

Even before customer AI, business models have been propagating across sectors. Our annual events, SubscriptionX (17 June, London) and ChannelX, chart the adoption of subscription, membership, loyalty and recurring revenue models in retail, along with marketplaces, social commerce and new agentic channels. Digital capabilities, along with customer understanding, mean the models can “cross the ‘brane’” with high acceptance and relevance.

Life-domains replace sectors

As all products are under our thumbs, and all relevant business models are available, consumers organise their lives around recurring domains of experience or life-events: Friday Night In, Leisure, Coping & convenience, Health & wellbeing, Hope, futures and ageing

This means that multiple sector players and multiple business and experience models all now converge on the customer. Take the “Friday night” scenario of a sociable evening at home with friends. To make the evening a success, we can imagine:

Netflix (subscription model, streaming data)

Pepsico for snacks and treats that are linked to watching TV (brand-direct selling)

Co-op or another supermarket for dinner or extended snacks and beers, working with

Deliveroo (Q-delivery, but with a subscription and promotional model) to get the basket to your sofa

Diageo (controlled product, age-restricted) markets liquor as a ‘night-cap’ or pre-clubbing option

Uber to get your friends home or to the next activity.

These individual businesses can work together via formal partnerships, retail media campaigns (where customer and product data can be shared through promotional marketing), and with Agentic AI, which creates and coordinates products, models, locations, data, orchestration, and experience.

What does “winning” now mean?

Today’s senior leaders grew up with the question “How do we win in our sector?” This is no longer a good enough question since in-sector optimisation is at a peak. Rather, growth needs to come from outside the current sector. The good news is that it’s never been easier to target, appear, and transact in other domains. The bad news is that the total amount of new revenue is finite - the customer has no more than her disposable income and it can only be spent once.

The customer has shown, by her actions and expressed intention, that she is willing to shop across sectors - whether this is due to her AI being able to bring providers together with ease and speed, the dissolution of barriers, or the increase in cross-sector capabilities.

It’s not the time for the direct-selling businesses to determine how they will respond. There are three options:

Copy. Simply adopt business models, approaches, and methods from successful players in other sectors and enter as an already-capable clone.

Collaborate. This is most easily done where your product is complementary - then you are sharing from an enlarged pie.

Compete. Whether through copying, post-collaboration refinement or a new angle for existing demand, entering new sectors with the intent of dominating them is a punchy and admirable approach.

In reality, the ambitious retailer, grocer, hotelier, travelmonger, banker, broadcaster or gamer will be looking to do all three, based on opportunity, capability and creativity.

CustomerX

After a long walk, this is the reason that we’ve created CustomerX (live at Olympia, London, 14-15 October 2026).

The customer is unbound by sector barriers - a combination of customer-driven agentic AI, cross-sector marketing promises and collaborations, and a growing sophistication in delivery. The legacy differences between sectors make limited sense or benefit now that mobile and AI agents sweep magestically all buyable surfaces

Developments like Google’s Unified Commerce Protocol (UCP) - our topic for the next newsletter - provide a basis to sell, connect, collaborate and deliver across all surfaces, not just your own website or existing marketplace relationships. The humble product is freed to be seen, bought, enjoyed by any agent, any time, within the service parameters

Inventive initiatives to inhabit the customer’s life - around social events (‘Friday night’), leisure (health data plus Strava and mapping, meet Nike and your local gym or football field) or travel (your smart luggage knows your BA Club details, hotel, restaurant choices and your seat at Taylor Swift gig you’ve travelled to enjoy).

The business models flex to support enjoyment - your swimming pool’s monitoring system becomes home security peace of mind, while your washing machine chats with Miele engineers and orders washing liquids, a service and chats with Octopus about your energy usage.

In this world - cross-sector, multi-business-model, collaborating and customer-centred - CustomerX is where commercial leaders who seek the consumer’s discretionary spend meet to learn, be inspired and do business.

This year, our research, podcasts, analysis, and interactions will be aligned around the core commercial question: “How do we remain relevant in our customers’ lives as intent becomes fluid and decisions accelerate?” Via partnerships, use of technology, leveraging data and honing our narratives, we can compete in the exciting and relevant cross-sector commercial world.

The old silos have already dissolved.

I look forward to your thoughts and insights on the CustomerX world.

The UK uses the UN definition of spending, namely the “Classification of Individual Consumption by Purpose’, or COICOP. There are 12 categories (detailed here) and the following chart and table give the values for 2024 in the UK (£GBP). If you want European data there is an explorer option giving all countries to 2018. Back to the UK, here is the annual “disposal” income for FYE 2024, analysed further by income quintiles:

This is how the money was spent:

Note that the definition of “disposable income” means “all money after tax”. I would make a distinction with “discretionary spend”, being money that you have some choice over where, whether and how much to spend. Housing (category 04) is not really an option, and most transport is for car ownership and commuting, so an adjusted level for ‘discretionary spend’ would be an average of c£46,000 per annum per family

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Allegory_of_the_cave

Source: https://www.reddit.com/r/chemicalreactiongifs/comments/4fv0ti/acetone_dissolving_styrofoam_cup/

Brilliant metaphor work here. The dual chemistry of AI as solvent and accelerant captures how it's not just removing barriers but actively speeding realocation of attention. What intrigues me is the asymmetry, where frontends collapse into horizontal experiences while backends stay rigidly vertical. That gap creates coordination costs that agentic interfaces dunno yet how to absorb, especailly when logistics and regulation differ so wildly across sectors.